Over the past four decades the world has seen the privatisation of health and other social services. Stemming from the ‘Structural Adjustment Programmes’ that the IMF, World Bank and other international financial institutions imposed on countries of the Global South, as well as the attacks on unions and other democratic avenues for social accountability in the Global North, people around the globe have been forced into private health services.

‘Forced’ is the operative term. The notion of free choice in a health market doesn’t really apply to parents of an ailing child, or to anybody in an ambulance, if she or he can afford one. Even a healthy person going for a routine check-up is less a ‘consumer’ with choice as opposed to a source of raw material for tests and procedures that commercialised health care applies to everyone with a wallet.

Yet, the prevailing narrative – espoused by Global North governments and financial institutions, and largely accepted by Global South governments and NGOs – has been that private markets and individual choice are the answer. But, what was the question, if not a challenge to social accountability or democracy (recalling the infamous neoliberal treatise from the Trilateral Commission)? Thinking back a few decades, perhaps, “how to reign in governments that spend funds to serve their people?” Or, “what is the best way to forestall further gains in racial, gender and social equity, with implicit fears of an ‘excess of democracy’?”

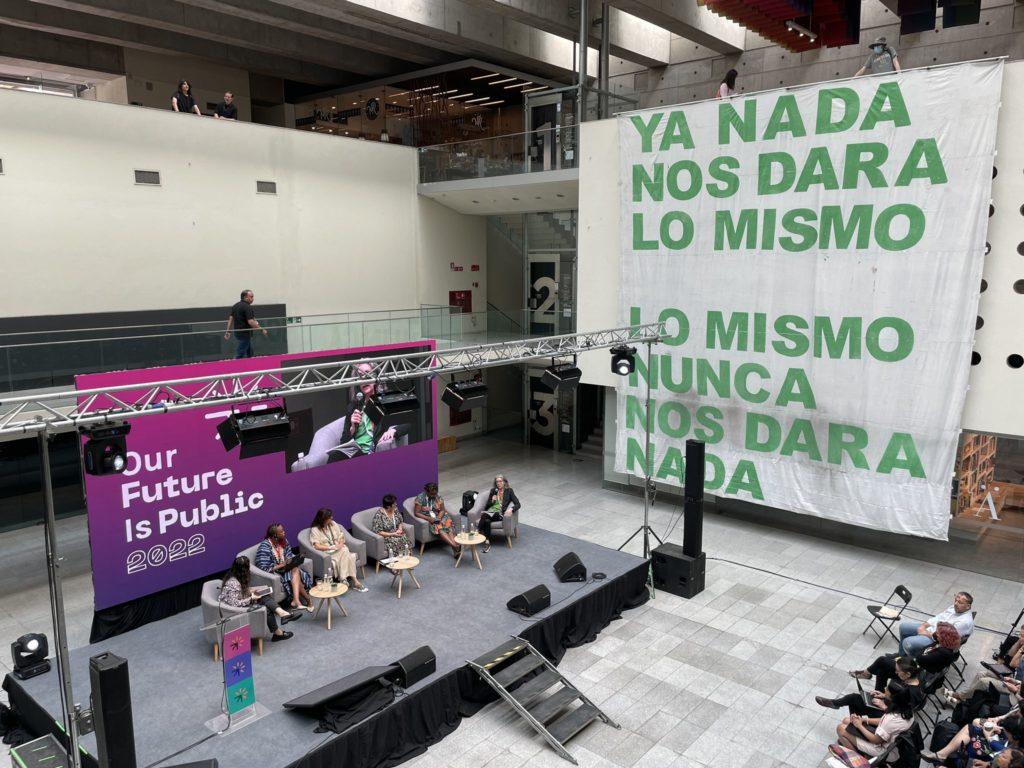

The Our Future is Public conference brought together health and social sector professionals, academics and activists in Santiago, Chile (29 Nov-2 Dec 2022), to challenge that failed narrative and rechart a public commitment to essential social services. With leadership from Magdalena Sepúlveda of the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the conference addressed economic justice, social protection, education, care, energy, transportation, food and agriculture, housing, and water – with cross-cutting discussions on gender, climate change, tax justice and democratic ownership. Some participants commented that it is rare to find so many sectors in a single convening, though Baba Aye and others at Public Services International pointed out that they often bring together workers across many sectors.

The authors, Ravi Ram and Leigh Haynes, attended the conference, and Leigh joined Rossella de Falco of the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in guiding the health sector participants through an agenda with lively debates on the principles of public vs private health services and financing and the consequences of policies that support either approach. Participants traced the rise of privatised health services to governments’ abdication of their core role in meeting basic social needs and fulfilling health rights among other economic and social rights. That in turn is traced to donor-driven development, with the Global North imposing a privatised health model on the Global South – even as most northern governments ignore that advice in their own policies. The Covid-19 pandemic exposed these contradictions through the commercially driven inequities in vaccines and other health technologies between the self-privileged minority world of the Global North and the majority world of the Global South.

In a series of presentations, facilitated sessions, site visits and informal discussions, the health sector participants worked to identify the core challenges limiting public services and demands that will lead to realisation of a truly healthy, public future. These centered around three themes: people, money and ideas.

People

A people-centered health system focuses on individuals, families, communities and health and care workers as the most important drivers of the health system. People are empowered to meet their health needs, and resources are mobilized to support people’s health, for instance through tax justice, health promotion, and equitable access to nutritious foods, safe water and shelter. By contrast, a privatised, commercial health system ultimately prioritises profits, as we see in countries around the world, rather than putting people and people’s health and well-being first in any decisions. The result is a focus on profitable treatments for disease, rather than prevention or promotion.

The power disparities in the prevailing health system exclude people and health workers from participating in decisions that affect their health, prioritising commercial profit and notional efficiencies over health rights and health equity. With a weak state that fails to provide health services to all, private and commercial actors use health to generate profits for the few, with a narrow market-focus restricted to those who can pay for quality services. This approach has seen a rise in health inequities, linked to the privatisation of other social sectors that affect people’s health such as housing, education, water and sanitation, because private actors operate in an absence of democratic, social accountability. Participants in the health sector meeting agreed that to decolonise health and promote health rights and equity – nationally and globally – it is critical that health systems and financing place people and health workers at the centre: the voices of patients, their families and communities, and health and care workers must frame the functioning and financing of an equitable, people-first health system. Governments and international institutions, with the participation of civil society and people affected by their decisions, must work towards developing formal mechanisms for accountability and social participation in health.

Money

Transnational corporations, philanthrocapitalists and international financial corporations wield unaccountable power over health. They shape tax and health financing in the Global North and manipulate development institutions and ‘aid’ programs to create favourable ‘market conditions’ through conditionalities, fiscal consolidation and austerity on health financing in the Global South. Further, this unaccountable power in global health undermines public provision of health and other essential services in pursuit of profits. Increasingly privatised and commercialised health services have led to overpriced, medicalized care for the few, inadequate care for the majority, and an absence of health promotion for all. Health sector participants noted the lack of financial justice in health. To start down a path towards financial justice, participants concurred that financing and provision of health care and services should be publicly funded, equally for all peoples, based on an equitable, progressive tax system that works in solidarity across countries.

Ideas

Health is inextricably linked to all of human experience. While that idea resonates as common sense, much of global health has been led to see the opposite: that health is an option to be purchased. That premise supports a narrative that equates privatised health with quality and public services as second-best, relegated to the poor. In particular, health promotion and disease prevention are critical aspects of public health that do not fit in a market system; care and treatment can be commercialised only if health equity is discarded. Therefore, the narrative that publicly provided health services are an inferior choice must be remedied. Only by ensuring that publicly provided health services have sufficient resources can health rights and equity be realised.

The private-first approach has been promoted by the Global North and imposed on the Global South – as well as on the poor in any country. That approach is at its core a political problem – not a technical problem – and requires a political solution. The political dimension demands a decolonization of international institutions and of the global health architecture and financing.

Other related civil society actions that were highlighted at the conference include the launch of the Global Public Investment (GPI) Network, with Simon Reid-Henry,, Alicia Ely-Yamin and the Joep Lange Institute. The Kampala Initiative had previously hosted a discussion on GPI, and expressed interest in a follow-up webinar on the new network.

The health sector meeting concluded with a set of demands, for civil society to carry forward in reforming models of health care delivery and financing:

What comes next?

Our Future is Public conference participants developed, across sectors, the Santiago Declaration for Public Services, which was published following the conference. The document expresses the collective vision of what a true “public future” looks like, what’s necessary to achieve this future, and actions conference participants will take towards that end. The Declaration is also open for endorsements.

The Santiago Declaration calls for action across sectors, and health sector participants commit to taking actions in our work to ensure that health, as the Declaration says, “is out of private control, and under decolonial forms of collective, transparent and democratic control.” Health sector participants will work to strengthen our movement against the commercialisation of health by providing information to the public and demand strengthened public health services. Participants agreed to build this network and strategically engage in advocacy for public financing and provision of health care. Finally, acknowledging the strength of public pressure, health activists will work to build at the grassroots level through providing information to the public about the human rights harming effects of commercialization of health.

In order to achieve the right to health for all, the future of health must be public.