Decolonisation is not a metaphor and decoloniality is not an end. Rather, it is a means, a segue, a process, a lens with multiple ends. To advance socially just health systems, we argue for global health scholars (and especially us located in postcolonial contexts) to take a political stance on the side of justice. We need to recognise that we have the agency to read, engage with, and apply decolonial theory, methodology and praxis for justice and equity. Decoloniality requires us to be brave at chipping away, disrupting and dismantling but we also need to be realigning, building, reimagining and transforming in very real and concrete ways. At the African Health Systems Africa Convening 2020, Pascale Allotey asked: “how brave are we in the quest for the disruption of coloniality? How disruptive are we prepared to be?” It’s a vital question.

The predecessors of “global health” (among others, “tropical medicine”) were an instrument of colonisation, and global health has never fully shed this past. Through the systems and structures put in place by the colonisers, tropical medicine was instrumentalized to support the colonists’ overall aim to dominate, steal, loot, destroy, occupy, manipulate and oppress. More significantly, the colonisers’ oppression extended to destroying and changing our ways of being, doing, thinking. Their rule fundamentally changed and controlled our spirituality, bodies, politics, economics and connection to land. They re-oriented our systems to serve white supremacy, the project of modernity, capitalism and industrialisation. These created conditions of hegemony, structural violence, and oppression that are infused in institutions such as universities (schools of tropical medicine, anthropology, geography, architecture, philosophy and economics, amongst others), health care systems, policy structures, social welfare systems, arts, religion and language. These models – Ramón Grosfoguel calls them Westernised Universities – have been replicated in all countries that were colonised. Most of us are “products” of these Westernised Universities and are part of the legacy of colonisation. In other words, we ourselves are “colonised” – we have undergone processes of alienation, othering, and dehumanization. Many of us have been categorised and othered, racialized and gendered. The knowledge and lessons from our ancestors have been demonised and destroyed, affecting our identity and humanity in the process. To some extent, things changed for the better under tropical medicine’s successors, ‘international’ and ‘global health’, but as the current Decolonize global health movement rightly argues, not nearly enough. Indeed, by and large the same patterns continued after colonisation, though framed more euphemistically. Decolonial scholar, Nelson Maldonado-Torres refers to this as “coloniality”.

Meanwhile, in the current Anthropocene, our biosocial relations are markedly structured by a ‘capitalist world-ecology, joining power, capital, and nature as an entwined whole’. Under global capitalism, modernist paradigms of technological utopianism and economic growth have come to represent the ‘natural order of things’ . Placing this concept of “biosocial relations” in a wider context, we (humans) are responsible for the destruction and alteration of the earth’s atmospheric, geologic, hydrologic, biospheric and other earth system processes, from which we are also alienated. We human beings have thus also “colonized” the planet, with deep implications for our health. Put differently: we need to “decolonize the Anthropocene” as well. Soon.

Many would argue that the Global Health community (including many researchers and practitioners) has made significant progress in recent decades in improving health outcomes, reducing infant and child mortality rates across the world and raising life expectancy. In crude terms, the epidemiological transition is testament to these global health successes. Furthermore, fields like HPSR have advanced thinking in health systems strengthening. However, when we examine the entrenched inequalities using an intersectionality and decolonial lens, the evidence of coloniality soon starts to emerge.

Using an intersectionality and decolonial lens to analyse entrenched inequalities reveals how coloniality still permeates the systems and structures that global health is nested in. Along the lines of feminist scholar and activist Audre Lorde‘s metaphor of the ‘Master’s House’, we consider Global Health also a ‘Master’s House’, as it decides “who gets to live and who gets to die”, through various pathways ( resource allocation, norm setting, health research & priority setting, …). This should compel us to assess how Global Health still upholds the colonial footprint. And then deal with it. At the already mentioned African HSG convening, Professor Faisal Garba raised our awareness of the dangers of commodified health, while Professor Elewani Ramugondo descibed racism (which continues to operate within global health categories, implicitly or explicitly), as genocidal. Many scholars have linked capitalism, profit-driven pharmaceutical companies, burgeoning private health care, dependency on philanthrocapitalism, aid, donor funds, and vertical programs and selective primary health care. Although many Global Health interventions appear “helpful”, saving the lives of African children, the real commitments usually fall short of the lofty rhetoric, and fail to address deeper structural inequities. This reaffirms the political nature of health systems and policies (with ideology never far away). Dominant tools and methods of research and practices of global health are more often than not, neo-colonial, neo-liberal and complicit in reinforcing hegemonic systems of power. It remains thus imperative to interrogate the ‘master’s tools’.

Audre Lorde offered a powerful word of caution when she stated, ‘for the Master’s Tools will never dismantle the Master’s House. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change’ (1984, 110–11). The dismantling of the ‘master’s house’ – that is, colonial ideologies and traditions that are imbued within our psyche and entrenched in our systems – only threatens those who still define the Master’s house as their only source of possibilities, solutions, or support. For Lorde, the tools of resistance and building formed within prevailing practices, structures, and institutions are ultimately unusable for the task of overturning the hegemonic conditions that prevail. The re-imagining project requires different sets of tools. Therefore, Global Health scholars cannot continue using the master’s tools and be confident that they are dismantling the master’s house.

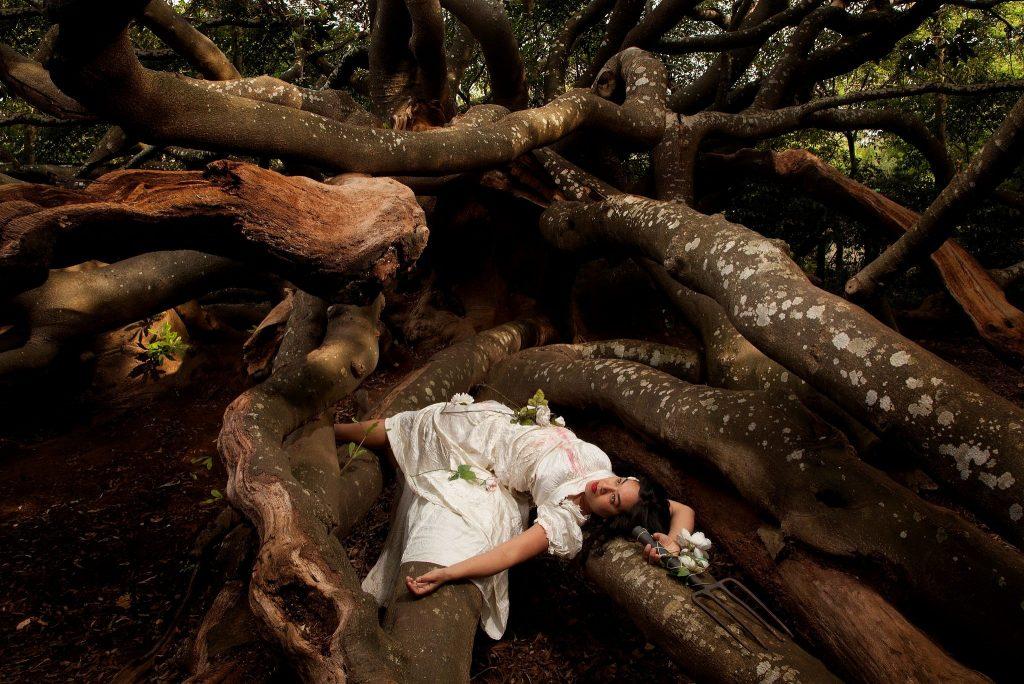

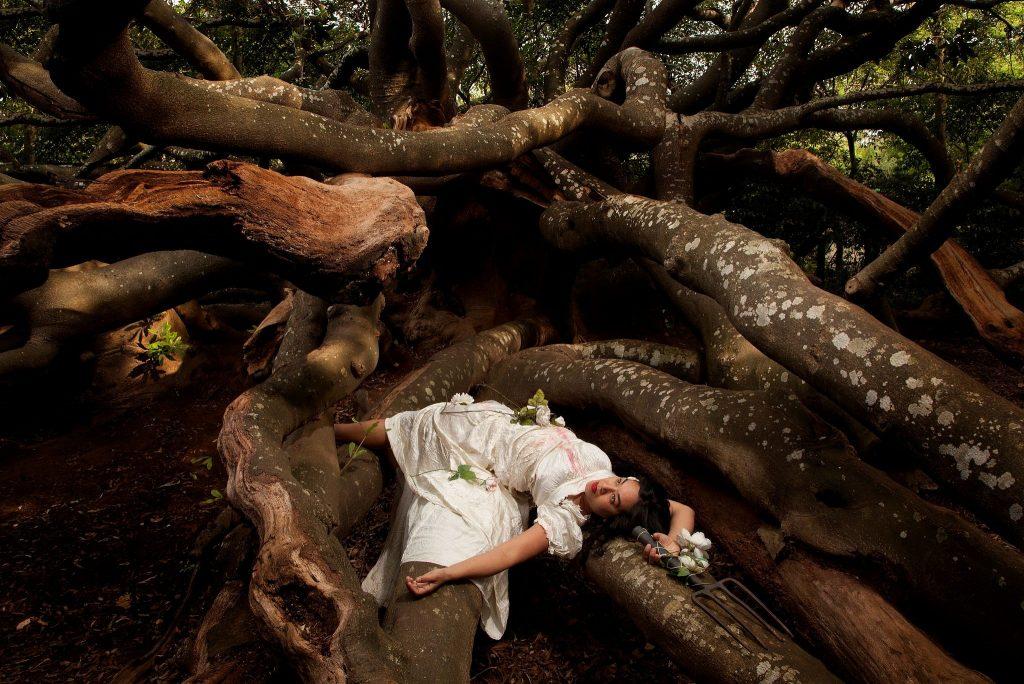

To truly decolonize, global health scholars must seek genuine measures of resistance and liberation. For Lorde, this must come from somewhere else, somewhere “outside,” whether outside of “the western canon,” outside of mainstream academia, outside of modern political institutions, structures, and social processes, or perhaps outside of history altogether. And we would argue, probably outside of “global health” as well.

For African scholars situated in “global health”, we thus propose an African consciousness project that centres the wealth of African philosophies, knowledge, cosmologies, praxis, ways of being and doing from the multiplicity of contexts on the continent as worthy of inquiry and as valid and important for our own healing, wellbeing and health.

Decolonisation requires application. We need to reconfigure the master’s tools to transform the master’s house. We need to be intentional about examining the tools we use in our theory, praxis, but also in our ways of being and doing. Global health needs to find a language in which we can describe how we are resisting and challenging hegemonic practices and forms of power. This language needs to translate into the discovering and development of tools for overturning the hegemonic conditions that still prevail in global health. We need to look to archives outside the Western canon that will help us liberate and rehumanise ourselves. Using this new lens, we can then begin reimagining health, outside of profits, outside of “outcomes” and ‘’deliverables”, but rather, as a way to celebrate our humanity in all its diversity. The language of radical love, care, collective reliance, compassion, reciprocity, justice and equity should become the cornerstone of how we approach global health.

Pascale Allotey asked us to be brave, and ready for a slow, difficult process. However, she emphasized, if this is done with integrity, it can lead to transformation. And, as we would add, to a real “Re-imagining of our health systems”.

PS: recordings from the HSG Africa convening (see https://africanhealthfutures.co.za/ ) will soon be available.