The field of Health Policy System Research (HPSR) offers us valuable theorisations and empirical work to guide us on how we can engage with the complex social, economic and political nature of health systems today. However, the field has not been able to fully grapple with theblind spots that are ever present in our reality. This is why we argue that more needs to be done to actively build the capacity of HPSR scholars to question the implied assumptions of the dominant discourse that helps us make sense of the world we inhabit.

There is no turning back

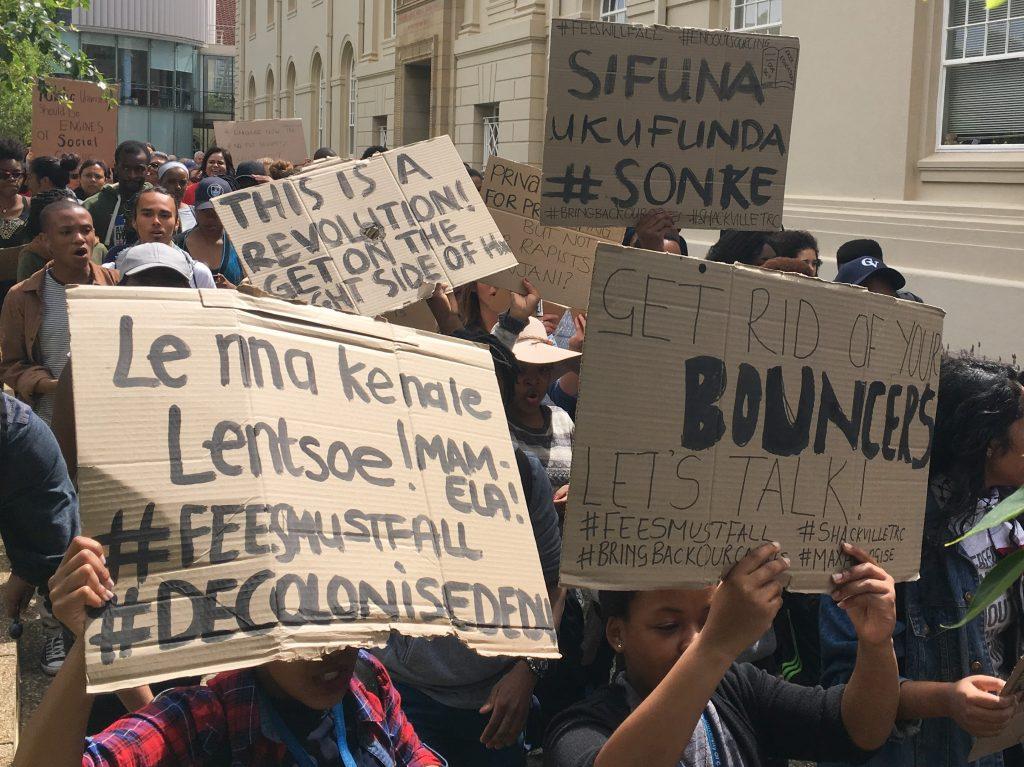

As African HPSR scholars, practitioners and advocates, we feel it is time to build our collective capacity to engage in critical decolonial studies in order to develop counter power strategies that can inform the reorientation of health systems to be responsive to the issues of African localities. While the importance of decolonial perspectives linked to HPSR and global health has emerged in conversations, much of these discussions and ideas have been concentrated in well-resourced global north institutions such as Harvard University and Duke University (with an event coming up on 31 January). Contrary to what the colonial project has intended, as Africans, we have a responsibility to shift our focus continentally to build solidarity with efforts to break silos and divides that exist across diverse African contexts and to re-orient African knowledge, realities and people as valuable and legitimate knowledge bearers. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, a prominent professor at the University of South Africa, warns against the word decolonisation becoming a buzzword and a metaphor. Instead, he says “decolonisation has to remain a revolutionary term with theoretical and practical value”. As Africans, we need to foreground our narratives, engage authentically and honestly, and make space for difficult conversations about power and hegemonic epistemologies.

Questioning implied assumptions and developing new tools and practices

We offer three strategies as starting points to advance the conversation; framing, voice and space and praxis.

Framing

Decolonial scholar Grosfoguel explains how the structure of knowledge in westernized universities is built on the destruction of knowledge systems, “epistemicides”, at the start of the modern/colonial project. For example, the burning of libraries in places like Al-Andalus. This led to the creation of the hegemonic Westernised frame based on modernism founded on Descartes’ most famous phrase “I think therefore I am”. The fields of global health, HPSR, colonial medicine along with anthropology, sociology have been generated with a Eurocentric/North American frame within the terrain of the overall project of modernity and industrialisation. While many of these fields have tried to move away from their violent past, towards values of social justice, many fundamental issues continue to exist. Professor Maureen Mackintosh from Open University wrote a blog critiquing “global health” framings of low-and-middle-income countries’ populations, researchers, activists and professionals as recipients of in-bound knowledge and technologies, or as empirical fodder for Western theoretical framings. Madhukar Pai shared examples of how parachute research and global health consulting mimic colonial ways. Seye Abimbola unpacked some of the imbalances in academic global health and pointed to the problem of the foreign gaze. HPSR researchers who are taught in neoliberal universities with a eurocentric approach operate on a market driven approach that defines how knowledge is produced, generated, commodified and held. The knowledge held informs how health systems are organised – often as colonial institutions. Furthermore, the westernised university does not draw on indigenous ways of being and doing.

In order for African HPSR scholars to unsettle this form of coloniality of knowledge, power and being, we need to name and engage explicitly with the hidden powers and different types of power that operate to reinforce coloniality in our research. Walter Mignolo calls this process epistemic disobedience. Despite our good intentions, we need to understand the parameters in which we operate and think and recognise how they are informed by our lived experiences and positionality. This means we need to critically reflect and be reflexive on how our training, research and practices perpetuate the very systems of oppression underlying global health and colonial medicine. The practice of recognising our own frame and the frame of the authors we read, will enable us to move away from stereotypes that exist within ourselves about ourselves, and decentre “weaknesses” constructed by and through colonialism, patriarchy, racism, white/western/European/North American hegemony, heteronormativity, sexism and neoliberalism. Professor Helen Schneider provides one example of how HPSR researchers can reflect on positionality. In a section entitled “embedded researcher” (pg. 40) of her PhD, she recognises that where she is positioned shapes how she sees the “problem” of a health system and therefore the priorities for research. She shares her story and declares the multiple factors that shaped her “approach and orientation” to her research on Community Health Workers (CHWs) in South Africa. She invites us to recognise both her expertise and limits of her frame.

Voice and space

Maria Lugones, an Argentinian scholar, in her article “Towards a Decolonial Feminism” builds on the concept of coloniality of power, which Latin American scholar Quijano identified as the technologies of exploitation and violence, of the ‘colonial matrix of power that affects all dimensions of social life’’ by arguing for modernity and coloniality to be understood as simultaneously shaped through specific articulations of race, gender and sexuality. Feminist theories offer the concept of intersectionality that can enable HPSR scholars to understand how the intersection of ‘the matrix of power’ leads to the erasure of colonised women, especially black women, from social life. This has implications on whose voice is centered, and who is taking up space in the conversation.

In “Can the subaltern speak?”, Indian scholar Gaytri Spivak examines the relationship between Western discourses and the possibility of speaking ‘of’ or ‘for’ the subaltern. Subaltern, a concept rooted in post-colonial theory, describes the unequal power dynamics and relationships that previously colonised nations and populations have with Western centres of power. They are socially, politically, and geographically outside and separate from the centre of colonial power, and when researchers speak for them, Spivak describes this asepistemic violence because this mode of knowledge production is built on the idea of the universal that is displaced from the subaltern “other”, where the “other” is often written out of history, rendered as complacent, docile and passive. HPSR researchers need to reflect on the consequences of taking up too much voice and space, when there is a distance between HPSR research and the reality on the ground. These consequences are evasion, misrepresentation and self-deception. For example, researchers on CHWs often fall into this trap when our recommendations reproduce inequalities and totally disregard intersections of gender inequality, race, education, professionalisation and occupational hierarchies within the sector and the social and economic burden of unpaid labour. As Kristof Decoster highlighted in a recent IHP intro, decent work for all should be a key priority, going far beyond working conditions of health workers only.

Praxis

What this translates into is bringing forward the works of Bhaba, Spivak, Gurminder and Kilomba who argue that marginalised and indigenous voices need to be centred and that we need to be creating other ways of making sense of our world. Importantly, those working to transform this space should not shy away from audaciously claiming themselves as the authority on their lived experiences. This way of engaging aligns closely with what Ndlovu Gatsheni terms the process of healing and reclaiming one’s humanity.

Therefore, we call for and seek to explore the possibilities of an explicit knowledge paradigm that frames decolonial research in HPSR, drawing explicitly on decolonial theories and approaches. Such a knowledge paradigm should include anti-racist, critical race, black consciousness, queer, indigenous and African feminists perspectives. Such a knowledge paradigm will contribute to the re-orientation of HPSR and frames an intentional political project that foregrounds the legitimacy of African knowledges, theories, and subjectivities that function to advance socially just health systems. Decolonizing HPSR is a conscientization project, a rehumanisation project and a re-imagination project, one that is historical and political in nature, and that calls for a new language and new ways of being as scholars and practitioners. As Africans, we need to be brave enough to leave behind pre-existing models which do not serve us and focus our energies on constructing new epistemologies that can lead to a socially just and equitable world.

Note: Together with decolonial scholars from the Global South, we plan to host an organised session at the upcoming Sixth Global Symposium on Health Systems Research (HSR 2020). The title of the abstract that’s been accepted is ‘What does a socially just health system look like: an imaginative space?’