We are writing from the following places: Azania, The traditional lands of the Three Fires Confederacy of First Nations, which includes the Ojibwa, the Odawa, and the Potawatomie, the traditional lands of the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, Lūnaapéewak and Attawandaron peoples, on lands connected with the London Township and Sombra Treaties of 1796 and the Dish with One Spoon Covenant Wampum.

The conference “Critically Examining Decolonization: The Field of Global Health” (February 20, 2021) was born out of a desire to interrogate current discourses of decolonization. Many similar conferences in North America have not yet situated the land on which they have taken place by examining the settler-colonial dynamics of power. As Hurwitz & Bourque write on settler colonialism, “land, not labor, is key. In this system, Indigenous Peoples are literally replaced by settlers.” Through a keynote, two panels, a workshop and a Q&A session, we sought to examine the ways in which colonial power has shaped global health discourse and the interaction between settler and global colonialism. Furthermore, we hoped to imagine how medical learners and professionals can disrupt these power structures.

In many ways, this conference resembled writing a story. We started with a few medical students living in Canada seeking to deepen and question dominant narratives surrounding global health in medical education. If the planning of the conference was analogous to structuring a plot, the audience and panelists were the writers, filling the pages with rich discourse. In accordance with the importance of collective storytelling in decolonial work, we brought together perspectives of organizers and speakers to reflect on the major points of discourse in the conference and to highlight ongoing questions of what it means to decolonize, specifically in the field of global health.

Decolonization is a revolutionary term tied to struggle, resistance and sacrifice

“Until stolen land is relinquished, critical consciousness does not translate into action that disrupts settler colonialism.” Tuck and Yang, Decolonization is Not a Metaphor

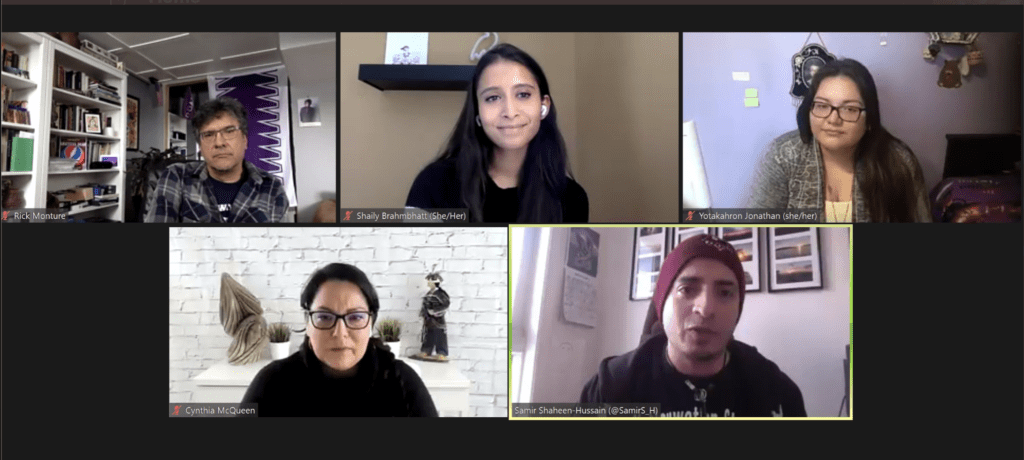

In the past year, calls to decolonize fields and educational institutions have entered mainstream conversation. However, we risk forgetting the most essential component of decolonization – the land and returning it to Indigenous Peoples, as noted by Dr. Rick Monture, an Associate Professor at McMaster University’s Indigenous Studies Program and panelist at our conference. Post-conference, some of the co-authors of this piece weighed in. On the spiritual pain associated with the dispossession of land, Shehnaz Munshi reflected, “When combined with sophisticated epistemic violence and colonisation of our minds, colonisation has devastating implications for physical, spiritual, emotional, social, and community health and well-being.” Additionally, Yotakahron Jonathan noted that “Settlers of Turtle Island need to recognize that personal sacrifices will need to be made and lived experiences need to be prioritized… we need to ensure that whoever’s land we are on, we are uplifting their voice.”

So, what does it mean to decolonize? Decolonization is a revolutionary term, as highlighted throughout our conference, and requires us to be willing to give up privilege, self-interest, land and control. This revolution is rooted in resistance, struggle, justice and mutual care; It requires an understanding of colonial history and a critical reflection of what purpose and who decolonization serves. It lies beyond conference discussions and academic circles and requires tangible action at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels.

Global vs. Public Health – Saviourism vs solidarity?

Panelists from the global South spoke about perceiving their work as public health work rather than global health work. If public health is located within and ‘done’ by local communities, is the term ‘global health’ inextricably associated with the “imperialist complex”? Yotakahron Jonathan reflected, “instead of being responsible for the health of the public in settler colonial societies, for example the health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, this distinction is a way to avoid accountability through true reconciliation.” In the context of the settler-colonial nation state Canada, the difference in terminology is a settler move to innocence. By portraying global health as an ‘elsewhere’ rather than ‘right here’ problem, institutions and individuals in the global North absolve themselves of the crucial discomfort created by the nature of decolonization and exacerbate white saviorism. Perhaps a new interpretation of global health is one that would be diametrically opposed to its persistent coloniality and lies in movements of shared solidarity against colonial powers, such as those of migrants and Indigenous Peoples in Canada, and “sharing of strategies of resistance” against ongoing occupations and colonial projects around the world.

Accountability is rooted in positionality and reflexivity – who are you, what is your relationship to the land and to whom are you accountable?

“It shouldn’t be on Indigenous people to do the work…it should be on settlers. Doing the work is part of the unsettlement that is needed. And asking this of Indigenous people or expecting us to keep them accountable, is another settler move to innocence. Reading lists, like the ones provided by this conference, should be seen only as an introduction to this work, not “the work” itself.” – Yotakahron Jonathan, Mohawk, Bear Clan from Six Nations of the Grand River Territory

“I am reminded of the tension within my own identity. My parents moved to North America from Tamil Nadu nearly fifty years after India gained independence from the British. Now an uninvited guest on Turtle Island, I think about the ways in which I am complicit in the settler colonial project, how my existence is used to justify diversity and the “Canadian mosaic” and downplay the ongoing settler colonial violence that persists to this day.” – Divya Santhanam, second-generation Tamil immigrant settler

“To believe that any work is unbiased is naive. Colonialism is rooted into every aspect of my life and it is hard to conceptualize how much it influences my thoughts, emotions and actions. Reflexivity is the key to analyzing these influences to deconstruct its influence on me. This is not an easy task or one that is done quickly.”- Amadene Woolsey, third generation Caucasian settler from Austria and the United Kingdom

“Ultimately, we are accountable to communities and people. This must be centered in all of our work, be it local or global. We are moving beyond acknowledging our positionality alone, but towards a critical understanding of the dynamics of power and privilege in everything and how we are complicit in upholding these imbalances if we are not actively resisting them.” – Gopika Punchhi, second-generation immigrant settler from Mumbai

“Our speakers discussed the notion of radicality as a purposefully uncomfortable and unsettling idea. I felt tension between being a medical student being indoctrinated into a system with minimal power with the expectation to be complicit, and being radical and disputing the dominant narrative. We are expected to internalize the science and culture of medicine, but to critically assess the structures we exist in, is to antagonize them. I wondered, how can we as students stay radical in the ways in which learn and practice medicine?” – Anamika Mishra, first generation immigrant settler from Gujarat

If the process of this conference was likened to writing a story, it is certainly not sufficient; decolonization is not a linear process that can be achieved through checkboxes, but necessitates reflexivity, resistance and revolution. To truly decolonize, one must leap off the pages, into action.