Intro

(by Farchanda)

This year, the Face-to-face (F2F) part of the Emerging Voices (EV) venture was held in Medellin, Colombia from October 20-30, in the run-up to the 7th Global Health Systems Research symposium in Bogota. ‘Decolonizing Global Health’ is such a hot topic nowadays, that it could impossibly be left out of the ‘Big Talks’, a key component of the F2F program. But would you have expected that during this crucial session, the speaker would have been a white, somewhat older European male who stood and towered above the cohort of EVs and facilitators sitting on the ground, looking up at him? And yet, that was the case.

Some more background on the Big Talk (BT) perhaps: apart from being white and male, the speaker is also a former ITM staff member and was one of the facilitators during our F2F program. He further worked and lived in a Latin American country for almost two decades and has plenty of knowledge on Latin American decolonization literature and politics. The session was held at the main campus of the University of Antioquia in Medellin, in between our tour of the university’s facilities and amazing artwork, on Friday morning (October 28). After the speaker elaborated his thoughts on the topic, there was a bit of time left for questions from the cohort, but responses didn’t satisfy many of them.

Though the talk certainly left everyone thinking, we later found out that the thoughts amongst us were not as synchronous as some of us would have thought! The overall evaluation of the program on Sunday morning (30 October) pointed in the same direction. It was easy to find people who had had a negative experience of the – in their view – whole ordeal, but there were also others who were fairly neutral about the session or even absolutely loved it. Noteworthy as well is that there were some people who were so disturbed by the prospect of by whom and how the talk was going to be delivered, that they did not even attend and thus boycotted the session altogether. Conversely, a few EV facilitators even reckoned this was the ‘highlight of their EV journey’, especially in light of the location where the BT took place. Suffice to say: opinions diverged sharply on this particular BT.

Intrigued by what drove different EVs to have such differing perspectives, and also after some discussion with a few – slightly baffled – EV facilitators, I set out to find EVs from the different points of view who wanted to contribute to this blog. We didn’t succeed for all stances listed above, but nevertheless, together, our team of authors have tried to showcase the reasoning behind their diverse opinions. Who knows, after reading this blog, you might have changed yours?

(Fabu, Oluwatosin)

Speaking the truth is bitter and may be received poorly especially when the speaker happens to be from the category of the colonizers.

The speaker spoke HIS truth and therefore, we were able to understand how he has attempted decolonization of his mind and has positioned himself in the decolonizing of global health. He framed this by recounting his experiences of privilege from personal life and family, to work environment. Now it is our obligation as scientists to dissect this talk and accept that decolonization in global health is complex, and can only be addressed first from the psychological aspect before extending to other aspects of life.

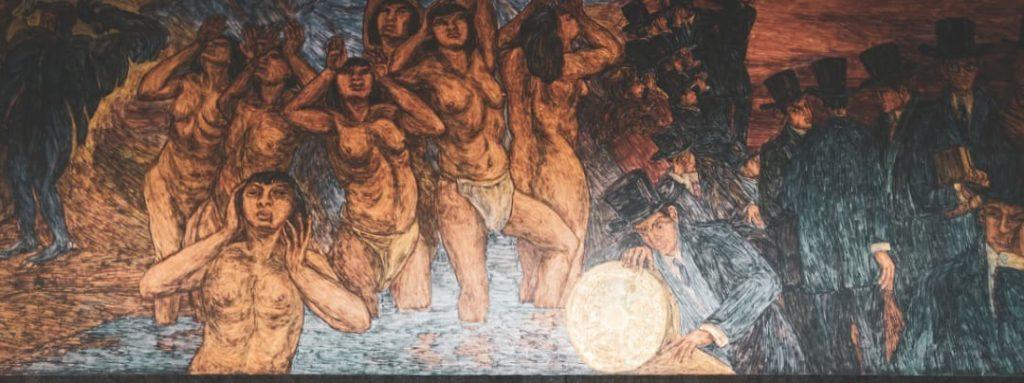

The University of Antioquia’s main campus was a fitting setting for this BT. Founded in 1803 by Spanish decree, the largest mural, spanning almost 40 meters of wall space outside of the library, was painted by Pedro Nel Gomez between 1968 and 1969. The inequalities between natives versus settlers, no doubt a reflection of the classist society in which the university was birthed, were evident in the mural titled “Man before the great discovery of science and nature”.

As we continued to the venue of the BT, we saw a campus in evolution from that first mural. A quote painted on the wall adjacent to where we settled for our BT, from Catholic priest, academic, and guerrillero Commander Camilo Torres read: “We should hold on to everything that unites us and get rid of everything that separates us.”

Many inequalities separated us during that BT, but there were also many things that united us. Chief among them was the opinion that the issue of decolonizing global health is one that is worth an ear, and a voice.

We are happy with the way the BT panned out because we were able to hear first-hand about privilege and see how it has affected conversations around decolonization outside of the space of those who have experienced colonization. This experience recalls why the fight for the decolonizing of global health must be owned by us in its entirety; but it is vital to create a space where everyone can be heard without being categorized, judged, discriminated, silenced or displaced. After all, isn’t that what we are fighting against?

Our allies cannot always be who we want them to be; they may draw comparisons to colonization based on what hits more closely to them. When the comparisons themselves highlight their privilege and distance from the real issue, that could be unnerving. Many allies may find it hard to understand that there IS a limit to their empathy and that no amount of authorships on published papers or citations of works on the subject could ever change that. This is why it is important for us to educate our allies, share our stories, discuss with them what we would like their support to look like and where we draw the line.

The movement towards decolonizing global health cannot just be rooted in research, it stems from lived experiences; but we also need to understand the rationale of those who are wittingly or unwittingly guilty of fueling colonial-esque practices.

However we decide to do it, our primary aim should not be to keep others out; it should be to fervently prevent dehumanizing this topic. As graffiti on the wall of the humanities building read: “There is no better way to achieve liberty than to fight for it.”- Simon Bolivar

(Ismael, Diane, Rizka)

From our perspective, the “BT” on Decolonizing Global Health generated controversial and meaningful discussions on a topic that risks becoming a “buzz” word. We consciously took a neutral viewpoint to try and contextualize the different perspectives without drawing quick conclusions. Applying Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model, one can visualize an individual’s interactions and reactions across micro, meso, and macro levels, such as with neighborhood surroundings, community, and societal context. For example, we could see the irony as the speaker, a “white” adult male, talked about decolonizing global health while many were seated uncomfortably on the ground. Although the speaker clearly described his position, we believe there was a lack of self-reflection on the environment and clarifying boundaries. However, we observed that all the viewpoints agreed on the salient aspects of the talk, the inequity caused by the structural and systemic constraints within global health.

The covid-19 pandemic enlightened many about the massive inequalities and inequities between the “haves” and “have-nots”, especially in relation to access to life-saving vaccines and medicines. The majority of countries in the global south struggled to find vaccines for their population, while the northern countries debated about expired vaccines. It is clear that these structural inequalities and inequities are a colonial legacy continuously perpetuated and this at micro, meso, and macro levels. However, how far is one willing to go in the causal chain to prove the perversive nature of colonial legacies within global health? The speaker liberally concluded on causal mechanisms between concepts, for example, the relationship between capitalism and decolonizing global health, to the audience’s chagrin. Capitalism, for one, could have been an interesting perspective to interrogate as a structural concept that facilitates discrimination or inequity in global health. However, most thought it was too farfetched to draw links with decolonizing global health and the lived experiences. We thought this was probably because drawing links with structural concepts like capitalism appears to absolve those who benefit from the structural discrimination and introduce themes like “everyone is affected”. Decolonizing global health is a complex term that evokes different emotions, understanding, and reactions that one needs to be cognizant of. Nevertheless, it is a crucial topic albeit with clear boundaries and frames that we should talk about, lest we maintain the status quo or imitate ostriches. In this case, debriefing sessions on the speaker’s points and counter-arguments could have been appropriate to hear from the different voices. After all, that is what the talk intended to achieve.

(Mark, Zaida)

From our vantage point, the “BT” exacerbated disempowerment and a lack of accountability in addition to causing discomfort (not to mention the ‘white smoke’ from the speaker’s cigarettes). What exactly is decolonization? What does it look like and what does it feel like? These are ongoing questions that were barely emphasized and that we feel must address because when we misunderstand words, we risk misunderstanding each other. While the speaker began by stating his positionality and worldviews, the arguments were focused on prescribing ‘what to do’ and ‘how to do’ things to ‘decolonize our thinking’ – for instance, the discussion revolved around “‘us’ not needing to conform to ‘western analytical frameworks’, and instead developing our own as a possible way to decolonize our minds. But these narratives are somewhat out of touch vis-à-vis publication realities.

‘Decolonization’ has become a phrase which is manipulated to suit the needs of the powerful elite, while erasing the lived experiences of those who historically have been disempowered: and this is what transcribed during the talk, in our opinion. At the core, decolonization involves the ‘cultural, psychological and economic freedom for indigenous people, with the goal of achieving indigenous sovereignty’. Therefore, indigenous people should be positioned as experts in any talks on decolonization – that is not to say that colonial beneficiaries should not be part of the conversation, rather there is a need to rethink and reframe what this entails. To paraphrase @Jairo_I_Funez decolonization is not about making room for colonized people to have a seat at the table, it is about destroying the table. In reflection, the BT felt like we were being invited to have a seat at the table – to listen to someone who had clearly stated his position as a beneficiary of a violent colonial past – and tell us as a group of EVs majorly from the Global South that we should decolonize ourselves… we felt like we were experiencing whitesplaining. As Tuck and Yang point out, a common strategy of ‘settler innocence’ is to push the ‘decolonize our minds’ narrative, a point which was made repeatedly during the BT. We felt this was problematic for three reasons. Firstly, in the spirit of capitalism and co-opting of language, this strategy can be used to seem radical and transformative, without prioritizing action. For example, a practical strategy is to change the curriculum to include works from BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) scholars – yet progress on this is slow and underdeveloped. Additionally, it risks shifting the responsibility to individuals and overlooking the power of institutions and systems in perpetuating colonized practices and values. Secondly, ‘thinking decolonization’ ignores our positions as professionals and our experiences of decolonization – which is related to our final point: Colonialism is an ongoing global project. As such, decolonization is a disruptive and possibly violent process often met with resistance from systems that continue to thrive on the oppression and exploitation of indigenous people. Thinking is not enough; we need to act. As EVs, we felt the BT would have been far more impactful, if the speaker (in recognizing his position) engaged with us in a collaborative dialogue rather than speaking down to us. Ask us, listen to our experience of healing ourselves, confronting our communities and systems and how we strive for transformation even in the face of formidable global challenges. Let us learn from each other and engage in the ways we can dismantle the systems of domination.

From our perspective, the BT failed to place our lived experiences in low- and middle-income countries (or previously colonized countries) at the center of the discourse and ignored the important lessons we may learn, both for the current recuperation efforts, but also for moving forward. The world failed to learn these lessons and many countries are now suffering as a result. We need to stop re-learning the lessons from the past, and instead durably include mechanisms to generate insights towards understanding the interplays of power, positionality and culture as a framework for tomorrow. There is so much to learn about decolonization, but the first step should come from the ‘descendants of colonizers’ – acknowledge the struggles their forefathers caused, reframe the mindset that they hold (or become self-aware of their unconscious internal biases), and create a healthy environment in which we could embark on a two-way communication and equitable partnership. While the speaker tried to do this by stating his position and taking accountability for his familial history, we feel more could have been done organizationally to create a healthy environment for open dialogue.

We know that the decolonization discussions make the Global North uncomfortable, but lest they know, we have been uncomfortable for as long as we can remember. Endure the discomfort, in this way, perhaps they might learn something.

So – this is Farchanda again speaking! -, did *your* opinion change?

Feel free to share your thoughts under this blog!

Acknowledgment: John De Maesschalck & Kristof Decoster provided editorial support for this blog.