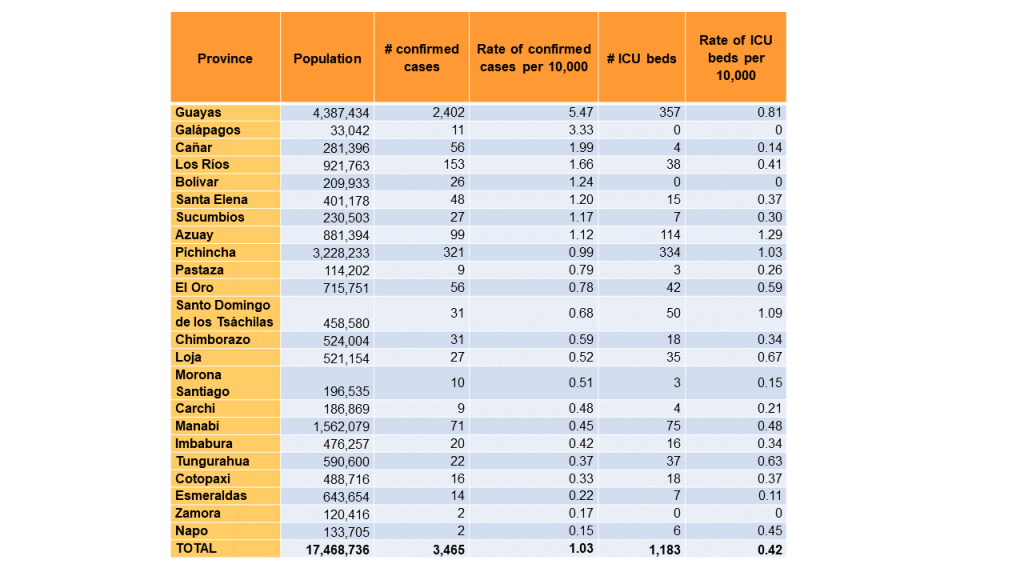

As Ecuador’s limited response to COVID-19 has hit the news in Europe and the USA, the country is still struggling to understand how everything may get even worse. By April 4, 2020, with 3,465 confirmed Covid-19 cases in the country, there were 172 confirmed COVID-19 deaths and another 147 deaths due to acute respiratory failure, most of them in Guayas, the most populated province (4.38 million or 25% of the total population), which also registers the highest number of confirmed cases (see Table). The second most populated province of Pichincha (3.22 million), where the capital city of Quito is located, has the second highest number of confirmed cases, but the number is far lower there (Table).

Since the first confirmed case was announced on February 29, Ecuador may be looking at a frightening scenario similar to Italy and Spain, particularly now that funeral services have been overwhelmed in the main hotspot, Guayas. The number of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests conducted until April 4 in Ecuador amounted to only 11.309 – in a country of 17.5 million people. In addition, there were only 68 intensive care beds per million people (total number of ICU beds in Ecuador: 1,183 – see Table) before COVID-19 mitigation efforts began, and some provinces had none. For the time being, 388 patients remain hospitalized and 139 are in critical condition. With 92.5% (16.2 million) of Ecuador’s population under the age of 65, COVID-19 cases have been recorded between under 1 year and 95 years of age; 45% of confirmed cases are women.

An unfavorable context

Before the COVID-19 epidemic, Ecuador had been undergoing continuous public budget cuts in the context of an economic downturn. The country has weak epidemiological surveillance, plus only 35 registered epidemiologists and 79 health professionals working as epidemiologists in the public sector. Moreover, as the COVID-19 epidemic escalated in this middle-income country, the government was slow to replace an inexperienced Minister of Health, and then opted for a physician and university professor who until recently practiced abroad. Contradicting global consensus, the Vice Minister of Health has promoted the use of chloroquine for prophylactic use by physicians and for medical treatment unrelated to clinical trials.

While it is clear that countries such as Germany and South Korea have been able to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 with massive testing, this is not an option for Ecuador, as it lacks laboratory capacity and must import all materials and most equipment required for such tests. Even if thousands of tests were to arrive as promised, current limitations of the health system make it difficult to enable systematic community testing. Therefore, the response has largely consisted in a national lockdown beginning on March 17, after 111 cases were confirmed. This has shown limited effect, however: by April 2, 1,538 people had already been sanctioned for not complying with the lockdown. There is pressure to procure foodstuffs and other essentials, and to continue with minimal productive activities, in particular within the more disadvantaged populations. In addition, internal migrants are attempting to leave the main hotspot. This is probably also the case for a high percentage of Ecuador’s 350,000 Venezuelan refugees living in extreme conditions.

Intersectional determinants

Ecuador’s health system is highly fragmented, segmented and unequal, with only 41.6% of the population having public health insurance. As a consequence, out-of-pocket payments correspond to 41.4% of the total health budget in Ecuador. There is an insufficient number of primary healthcare facilities, and, although there are 22.23 physicians per 10,000 people (n=37,293), roughly 50% of physicians at this level within the Ministry of Health are compulsory year interns working in rural, peri-urban and small urban health centers. With 19,890 nurses (12.03 per 10,000) in the country in 2016, the ratio is about 1 nurse per 2 doctors, which is inferior to global recommendations. Additionally, Ecuador does not have a centralized system of medical records to adequately monitor and follow up COVID-19 confirmed cases, and trace contacts.

Smartphones are used by only 32.7% of the population, limiting self-reporting through the government’s app as well as more agile learning about COVID-19. Crucially, this means disadvantaged populations will also have more difficulties to adopt personal measures, including indigenous people for whom very limited information has been translated into only one of the 10 ethnic languages of Ecuador.

Table. COVID-19 confirmed cases until April 4, 2020 and ICU beds per province in Ecuador

Data sources: Statistical Registry of Health Resources and Activities of Ecuador, 2017; COVID-19 Situation Report #40. April 4, 2020.

Cracks in the system

A majority of confirmed COVID-19 cases are being treated by the Ministry of Health, which means that already disadvantaged (uninsured) populations are being cared for in the network that is most under pressure, therefore probably causing further health inequities (for example, with more deaths occurring in this sector). In addition, ICU care, required for critical COVID-19 patients, is expensive, which implies an added hit to the Ministry of Health.

Due to the limited information available, and the government’s (in)capacity to adequately collect and aggregate data, different prediction models that have circulated among academics are contradictory and have not been corroborated at different moments of the epidemic. And, no predictions have even been planned concerning the care of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, infants and children with or without comorbidities that aggravate COVID-19, and end stage renal patients. In short, we know very little and the government has still not formalized a COVID-19 expert commission similar to Argentina or Scotland.

A path forward

While taking into account technological and health system limitations in Ecuador, coordinated local data management of confirmed and suspected cases, and supporting monitoring and follow up, will become crucial to mitigation efforts –rapidly building a localized response focusing on scaling up testing and guiding local populations. The country is densely populated and land and basic mobile phones are ubiquitous, making it possible for community-based organizations and local public institutions to support community-based surveillance from existing infrastructure and using available resources. This could also aid in promoting environmental cleaning and disinfection of public places. In sum, a different strategy would allow to address the intersectional dimensions of COVID-19.

A major condition of a strong health system is sustaining a trusting, balanced, effective interrelation with communities; trust is especially crucial in confronting an emergency such as the current COVID pandemic. Health seeking and abiding by recommendations are essential to contain and mitigate the spread of COVID, which requires that people self-report and self-quarantine or –isolate, report infection to immediate contacts, and uphold social distancing practices. For this, the population needs to be updated, informed and supported continuously, and the spreading of rumors needs to be curbed.

Necessary immediate measures

Although Ecuador´s health system has not been previously described as fragile, the current COVID-19 epidemic has exacerbated its underlying weaknesses to the point that early on in the outbreak, the system has already reached the limits of capacity. This means the situation could become even more dramatic than in Italy or Spain, where the health system is stronger and better resourced and funded.

Time is of the essence, the government needs to make decisions on a response that does not rely solely on centralized communication through massive media and force, based on the fear of being detained or sanctioned. Further detentions even have the potential of exposing people to COVID-19 infection by transporting and concentrating a number of them in a single location.

Attention should not only be placed on the provinces with the highest number of cases (which should still be prioritized), but should also go to other provinces with confirmed cases. This is an opportunity to rapidly build the basis of a renewed epidemiological surveillance and public health force at primary health care level, in this way making up for its weakening in the past decade, and in particular focusing on addressing health inequities.

Finally, a localized response may aid in addressing other elements of the COVID-19 response that have remained invisible, such as psychosocial and other forms of support for the general population, including women and children affected by gender-based violence intensified by the lockdown.