At the start of my work for development, humanitarian NGOs (and today in academia), I studied and lived the post-colonial beliefs on development. After graduating as an economist in 1987, I began working in the Democratic Republic of Congo, then called Zaïre, in a large-scale project covering healthcare, road construction, water and sanitation, education, and agricultural production. It was kind of a “state within the state”. In those times, development led by national states, or even the military, often resulted in “white elephants” and widespread (inter)national corruption. This was followed by a shift towards the ‘trade, not aid’ agenda and structural adjustment programmes led by the World Bank and IMF. These often had a devastating effect on the public sector and access to healthcare in general in the poorest countries.

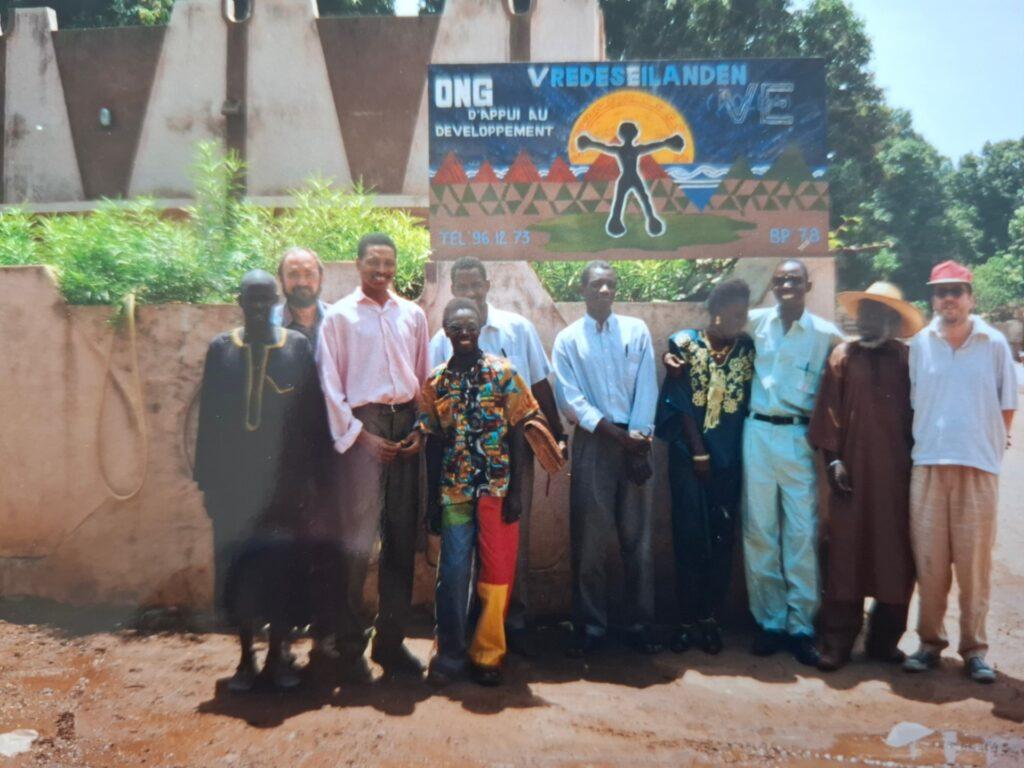

During the nineties, international NGOs took a prominent place, both the ‘structural development’ focused NGOs and the providers of humanitarian aid. Fortunately, the initial mistrust between both ebbed away over time, and the “local NGOs” in LMICs became gradually more important. They taught us to respect indigenous movements and to be culturally aware in our relationships. I’m happy to have contributed to the fair trade and alternative funding movements, which I consider to be sustainable initiatives.

When I joined MSF in 2003, I experienced a shift from apparently easy to understand conflict settings, to more complex ones involving many opposing players with unclear agendas. Alongside a decline in support for “northern” development NGOs working in the Global South, humanitarian NGOs lost the respect they once had on the ground. Humanitarian workers and their infrastructure are no longer safe. The continued violence towards humanitarian actors in Gaza is the saddest and most recent illustration of this.

At the start of the new millennium, most of us were optimistic, however. Thanks to Hans Rosling, we learned that in spite of an increasing world population, the majority of people now have access to education, life expectancy has increased and extreme poverty has declined dramatically. A significant proportion of the world’s population became ‘middle-class citizens’, and wealth became more accessible in many societies, with the exception of a few extremely wealthy and/or totalitarian ones. By then, we had also begun to talk about ‘failed states’. We had entered the era of globalisation, where the state, for-profit organisations and non-profit organisations were working together more closely than ever before.

By then, we had also entered a new geological era: the Anthropocene. While we were aware of the warnings in the Brundtland report about environmental protection in the 1980s, we failed to act upon them. In 2015, the UN prepared the ambitious Paris Agreement, in which many governments pledged to combat climate change and global warming — the most serious threat to global public health. Thanks to the Paris Agreement, more people became concerned and willing to make positive changes. Despite the discouraging efforts to block the way ahead in the COPs that followed, most recently in Brazil, I see ‘Paris’ as a turning point and refuse to be pessimistic.

At the start of 2026, we are again confronted with a new reality: an ‘America First’ strategy, including health interventions; the dismantling of the multilateral world architecture leading to more conflicts; and an increased denial of research outcomes, particularly with regard to the effects of global warming and how to combat it.

I suggest we see this as another “wake-up call”, and remember that societies are built by people, not politicians. Therefore, we must keep climate change on our collective and individual agendas and take many small steps forward. We should call for the democratisation of the UN and ensure that human rights remain at the core of our vision for a better world, in good health. Academic and non-governmental organisations must play their part here, in a smart way.

At an MSF directors’ meeting in Hong Kong in 2010